Museum Highlights

The Society’s Museum Director, Stephen McNeilly, introduces a selection of 13 highlights from the Swedenborg Collection, including items by William Blake, relics from the body of Swedenborg and rare letters involving the British Government. Photographs by The Quinn Fizzlers.

1. Swedenborg’s Walking stick

SWEDENBORG VISITED London on at least 7 different occasions, often staying for several years. On his final visit in 1771 he lodged at the house of his friend the wig maker Richard Shearsmith in Clerkenwell, where he died aged 84. Most of Swedenborg’s personal effects were returned to his family in Sweden, but several items remained including this copper tipped malacca walking stick which Swedenborg carried on his strolls through the capital. Shearsmith tells us that Swedenborg often attended dinners and social events and could be seen dressed in a full-bottomed wig, a pair of long-ruffles and a hilted sword.

SWEDENBORG VISITED London on at least 7 different occasions, often staying for several years. On his final visit in 1771 he lodged at the house of his friend the wig maker Richard Shearsmith in Clerkenwell, where he died aged 84. Most of Swedenborg’s personal effects were returned to his family in Sweden, but several items remained including this copper tipped malacca walking stick which Swedenborg carried on his strolls through the capital. Shearsmith tells us that Swedenborg often attended dinners and social events and could be seen dressed in a full-bottomed wig, a pair of long-ruffles and a hilted sword.

The fashion for walking sticks was introduced by Louis XIII with the preferred style being the ‘knob’ or ‘Tau’ handle, which would often display extravagant designs including precious stones and jewels. Swedenborg’s walking stick, in contrast, is quite modest, the one sign of luxury being the initials ‘E.S.’ engraved at the top. In his Rise and Progress of the New Jerusalem Church, Robert Hindmarsh (an early follower and founding member of the organized New Church) writes that the walking stick was purchased from Shearsmith by the Revd S Dean of Manchester, before finding its way via Hindmarsh into the Swedenborg House Collection. Swedenborg House has two other walking sticks that are thought to have been owned by Swedenborg but their provenance is uncertain.

“The fashion for walking sticks was introduced by Louis XIII with the preferred style being the ‘knob’ or ‘Tau’ handle, which would often display extravagant designs including precious stones and jewels.”

2. Swedenborg’s earbones

PERHAPS AMONG the strangest items in the Swedenborg Collection, the incus and malleus are the smallest bones in the human body and make up the inner ear. They work by picking up small vibrations and are therefore of special interest to students of Swedenborg in that he once wrote in an essay called On Tremulation in which he proposed the possibility of telepathy by means of thought vibrations. William White, an early biographer of Swedenborg, writes that they were collected from Swedenborg’s tomb from the vault of the Swedish Church in Princes Square, East London in 1790. The later found their way into the possession of Dr John Spurgin—friend of Keats and one time Chair and President of the Swedenborg Society.

PERHAPS AMONG the strangest items in the Swedenborg Collection, the incus and malleus are the smallest bones in the human body and make up the inner ear. They work by picking up small vibrations and are therefore of special interest to students of Swedenborg in that he once wrote in an essay called On Tremulation in which he proposed the possibility of telepathy by means of thought vibrations. William White, an early biographer of Swedenborg, writes that they were collected from Swedenborg’s tomb from the vault of the Swedish Church in Princes Square, East London in 1790. The later found their way into the possession of Dr John Spurgin—friend of Keats and one time Chair and President of the Swedenborg Society.

A minute from an 1881 Committee meeting at Swedenborg House notes: ‘on the table a walking stick which once belonged to Swedenborg and also an ear bone (in a case) originally in the possession of Dr Spurgin—both articles presented to the Society by Mrs Bateman’. Mrs Bateman was the widow of Henry Bateman (1806-80), the founder of New Church College, Islington.

“The earbones were collected on one of two occasions in 1790 when Swedenborg’s tomb was opened in the vault of the Swedish Church in Princes Square, East London.”

3. Fragment from the Spiritual Diary

BETWEEN 1747 AND 1765 Swedenborg kept a ledger or diary of his spiritual experiences. Although intended for private use only, these records have since been translated and printed into English, in 5 volumes, as The Spiritual Diary and are among the most original documents ever published. The majority of these handwritten manuscripts are kept at the Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm but a notebook containing some of the very first entries was lost.

“One day I opened The Spiritual Diary of Swedenborg, which I had not taken down for twenty years, and found all there”. W B Yeats

The sheet shown here—glued to the verso side of a frontispiece portrait of Swedenborg in the first English translation of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell—is a fragment from that notebook. Written in 1747, it refers to the spiritual significance of Gad and Asher, 2 of the 12 sons of Jacob, as described at chapter 49 of Genesis. At the bottom of the sheet, dated February 8 1757, Swedenborg notes: ‘on this day it was permitted me to note in the margin something concerning the blessings of the sons of Jacob, Genesis XLIX’. Before finding its way into the care of the Swedenborg Society, it was held by the Bath New Church where William Harbutt, made famous as the inventor of plasticine, published a small pamphlet on it. Because of this it is often referred to as the ‘Bath Fragment’.

4. Lock of Swedenborg’s hair

RICHARD SHEARSMITH, a professional wigmaker, once described Swedenborg’s hair as ‘approaching a pale auburn’ but for most of the time—at least in company—it was covered with a white peruke ‘as was the custom of the time’. Another description—given late in Swedenborg’s life—describes it as ‘grey’, and ‘protruding in all directions from under his wig’. The Swedenborg Collection has three samples, with the one shown here being the best preserved. The provenance of cuttings is uncertain although it is most likely they were taken from Swedenborg’s coffin when it was opened in 1790, at the same time as the ear bones were taken. A third was collected by Swedenborg’s close friend and confidant, Dr Messiter, and via a circuitous route, found its way into the Swedenborg Collection in 1907 from the granddaughter of C A Tulk.

“There is no image of Swedenborg without a wig, and from those portraits taken from life we see him depicted in a simple wig with short pigtail.”

“There is no image of Swedenborg without a wig, and from those portraits taken from life we see him depicted in a simple wig with short pigtail.”

Accompanying these cuttings in the Collection is a replica wig made in the style worn by Swedenborg. The wearing of wigs first came into high fashion in the seventeenth century via King Louis XIV of France who experienced hair loss at the early age of 17 and his English cousin, King Charles II, whose hair began to prematurely grey: both conditions were signs of the onset of syphilis. During the eighteenth century however wigs were worn by nearly all of the aristocracy across Europe with expensive wigs being been made from a mixture of human and horse hair, and powdered with starch, rice powder and plaster of Paris to protect against small insects. There is no image of Swedenborg without a wig, and from those portraits taken from life we see him depicted with a simple wig with short pigtail. Women did not wear wigs until around 1770.

5. Swedenborg’s Blotting paper

THE FIFTH item in this list is a fragment of parchment that, in the normal course of daily life, would have been used as kindling or thrown away. It was most likely caught between manuscript pages and discovered at a later date by happy accident. Made from a mixture of linen and cotton (paper made from wood pulp had yet to be invented), it would have been used by Swedenborg to gently absorb the occasional overflow of ink from his pen.

Given that Swedenborg wrote thousands upon thousands of manuscript pages, by hand and with a duck quill pen, it is surprising that more has not been said on his writing methods. Due to the sheer volume of material it was once suggested that he may have been ambidextrous but a close study of his manuscripts shows that this is almost certainly not true. Instead we see a neat style reserved for ‘fair copies’ (i.e. intended for the printers or for letter writing) and a rushed and uneven style reserved for topics of personal use. Both display a ‘right hand’ slant.

Given that Swedenborg wrote thousands upon thousands of manuscript pages, by hand and with a duck quill pen, it is surprising that more has not been said on his writing methods. Due to the sheer volume of material it was once suggested that he may have been ambidextrous but a close study of his manuscripts shows that this is almost certainly not true. Instead we see a neat style reserved for ‘fair copies’ (i.e. intended for the printers or for letter writing) and a rushed and uneven style reserved for topics of personal use. Both display a ‘right hand’ slant.

This small fragment of blotting paper was donated to the Swedenborg Society by Robert J Tilson (1857-1942), a former bishop in the General Church of the New Jerusalem and highlights the ephemeral and accidental nature of the Swedenborg Collection.

“Given that Swedenborg wrote thousands upon thousands of manuscript pages, by hand and with a duck quill pen, it is surprising that more has not been said on his writing methods.”

6. The Affidavit of Elizabeth and Richard Shearsmith

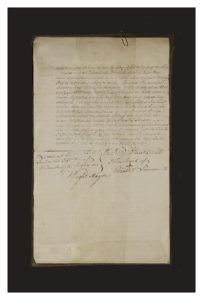

SWEDENBORG PASSED away peacefully on March 29th 1772, aged 84, at 5pm at the home of his friend and landlord Richard Shearsmith at no. 26 Cold Bath Fields. Signed and witnessed in the presence of Robert Hindmarsh and a Mr. Thomas Wright, Lord Mayor of London, this remarkable affidavit is a testimony of that event.

SWEDENBORG PASSED away peacefully on March 29th 1772, aged 84, at 5pm at the home of his friend and landlord Richard Shearsmith at no. 26 Cold Bath Fields. Signed and witnessed in the presence of Robert Hindmarsh and a Mr. Thomas Wright, Lord Mayor of London, this remarkable affidavit is a testimony of that event.

The affidavit of Elizabeth and Richard Shearsmith is important for several reasons. Firstly, it offers a rare and intimate portrait of Swedenborg’s living habits and final months in London, including the effects of a stroke and the moment of his passing. Secondly, it independently corresponds with John Wesley’s note that Swedenborg had anticipated the exact date and time of his final hour.

Shortly after Swedenborg’s death, a rumour was spread by a Revd Matthesius that Swedenborg had recanted and retracted his theological works. Robert Hindmarsh called upon the Shearsmiths in Cold Bath Fields to gain verification. The foreign clergyman mentioned, who ministered his last rights, was the Revd Ferelius, curate at the Swedish Church in Wapping where Swedenborg was interred. The affidavit was drafted by Hindmarsh. Elizabeth Shearsmith, unable to write, signed it with a ‘+’.

“The affidavit of Elizabeth and Richard Shearsmith is important because it offers a rare and intimate portrait of Swedenborg’s final months in London, including the moment of his passing.”

7. William Blake: Illustrations of the Book of Job and Eastcheap Minute Book

WILLIAM BLAKE remains the most celebrated reader of Swedenborg. He was the first poet to utilize the literary and aesthetic power of Swedenborg’s theory of correspondences and the first poet also to adopt aspects of Swedenborg’s literary style. One can even see an underlying Swedenborg theme in Blake’s most famous poem (and unofficial national anthem) Jerusalem.

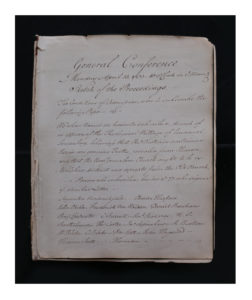

It is rumoured that Blake’s personal copies of Swedenborg’s books—now in the British Museum—were once in the care of the Swedenborg Collection. The reasons for handing them on are unclear, but the Swedenborg Collection does nevertheless hold an equally valuable item, and the only historical source linking Blake to any religious affiliation, namely a 1789 minute book from the first meeting of the New Jerusalem Church in Great Eastcheap. The meeting lasted four days during which there was drawn up a letter containing forty-two propositions or laws, which Blake signed. The original minute book is no longer extant but a copy, made at the time of the meeting, is still in the Swedenborg Collection and shows the place of Blake’s signature.

It is rumoured that Blake’s personal copies of Swedenborg’s books—now in the British Museum—were once in the care of the Swedenborg Collection. The reasons for handing them on are unclear, but the Swedenborg Collection does nevertheless hold an equally valuable item, and the only historical source linking Blake to any religious affiliation, namely a 1789 minute book from the first meeting of the New Jerusalem Church in Great Eastcheap. The meeting lasted four days during which there was drawn up a letter containing forty-two propositions or laws, which Blake signed. The original minute book is no longer extant but a copy, made at the time of the meeting, is still in the Swedenborg Collection and shows the place of Blake’s signature.

Also in the Swedenborg Collection are 5 etchings from Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job. The engravings were commissioned by John Linell and completed in 1825. An edition of 315 was produced in 1826. These were the last set of illustrations that Blake would complete.

“One can even see an underlying Swedenborgian theme in Blake’s most famous poem (and unofficial national anthem) Jerusalem.”

8. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: letter to C A Tulk and marginal writings

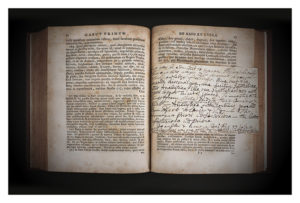

IT WAS VIA discussions with his friend Charles Augustus Tulk, one of the founders of the Swedenborg Society, that Samuel Taylor Coleridge first considered writing a series of books for the Society, including a ‘science of correspondences’ and ‘a history of the mind of Swedenborg’. Tulk is even said to have approached the governing committee with a proposal for Coleridge to be paid a retainer of £200. Famously (and sadly) the committee declined, thinking Coleridge not up to the task. The friendship between Coleridge and Tulk nevertheless continued and it was Tulk who introduced Coleridge to William Blake and John Flaxman, and it is from Tulk that we have the marginal notes written by Coleridge in copies of Swedenborg’s Oeconomia Regni Animalis (shown here) and Regnum Animale. Today Coleridge is famous for his marginalia. Friends would often loan him copies of their books with the hope that he would inscribe them with his thoughts and insights. The correspondence between Tulk and Coleridge also lasted for several years, with many letters still extant but now dispersed in multiple collections and archives.

IT WAS VIA discussions with his friend Charles Augustus Tulk, one of the founders of the Swedenborg Society, that Samuel Taylor Coleridge first considered writing a series of books for the Society, including a ‘science of correspondences’ and ‘a history of the mind of Swedenborg’. Tulk is even said to have approached the governing committee with a proposal for Coleridge to be paid a retainer of £200. Famously (and sadly) the committee declined, thinking Coleridge not up to the task. The friendship between Coleridge and Tulk nevertheless continued and it was Tulk who introduced Coleridge to William Blake and John Flaxman, and it is from Tulk that we have the marginal notes written by Coleridge in copies of Swedenborg’s Oeconomia Regni Animalis (shown here) and Regnum Animale. Today Coleridge is famous for his marginalia. Friends would often loan him copies of their books with the hope that he would inscribe them with his thoughts and insights. The correspondence between Tulk and Coleridge also lasted for several years, with many letters still extant but now dispersed in multiple collections and archives.

“Coleridge considered writing a series of books for the Swedenborg Society, including a ‘history of the mind of Swedenborg’. Sadly the committee declined, thinking Coleridge not up to the task.”

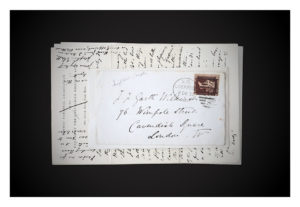

9. R W Emerson signed card and the Letters of James John Garth Wilkinson

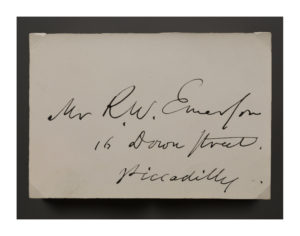

THE J J G WILKINSON correspondence within the Swedenborg Collection is worthy of a volume in itself. In total the archive holds over 1200 handwritten letters which include 86 to Henry James Sr, 20 to Thomas Lake Harris, 8 to R W Emerson plus many others including Coventry Patmore and John Ruskin. It was Wilkinson who introduced the work of Swedenborg to Thomas Carlyle and it was Wilkinson who was first to publish an independent collection of poems by William Blake. R W Emerson once described him as a man whose ‘vigour, understanding and imagination were equal to Francis Bacon’ and whose commentary on Swedenborg throws ‘all of the contemporary philosophy in England into shade’. Within this collection of letters there was also recently found, by our Archivist Alex Murray, this signed business card, collected when Emerson visited London in 1847. It was during this visit to England that Emerson gave his famous Swedenborg lecture, later published in his book Representative Men in 1850. The address, in Piccadilly, is still there today.

THE J J G WILKINSON correspondence within the Swedenborg Collection is worthy of a volume in itself. In total the archive holds over 1200 handwritten letters which include 86 to Henry James Sr, 20 to Thomas Lake Harris, 8 to R W Emerson plus many others including Coventry Patmore and John Ruskin. It was Wilkinson who introduced the work of Swedenborg to Thomas Carlyle and it was Wilkinson who was first to publish an independent collection of poems by William Blake. R W Emerson once described him as a man whose ‘vigour, understanding and imagination were equal to Francis Bacon’ and whose commentary on Swedenborg throws ‘all of the contemporary philosophy in England into shade’. Within this collection of letters there was also recently found, by our Archivist Alex Murray, this signed business card, collected when Emerson visited London in 1847. It was during this visit to England that Emerson gave his famous Swedenborg lecture, later published in his book Representative Men in 1850. The address, in Piccadilly, is still there today.

“It was Wilkinson who introduced the work of Swedenborg to Thomas Carlyle and was the first to publish an independent collection of poems by William Blake.”

10. John Flaxman: Miniature wax Portrait of Emanuel Swedenborg

As surprising as it might seem today, John Flaxman was once the most celebrated British sculptor of the early nineteenth century. Described by Goethe as ‘the idol of all dilettanti’ and a close friend of William Blake, he was also one of the central influences of the early spread of Swedenborgian thought in London during the late eighteenth century and one of the founding members of the Swedenborg Society.

As surprising as it might seem today, John Flaxman was once the most celebrated British sculptor of the early nineteenth century. Described by Goethe as ‘the idol of all dilettanti’ and a close friend of William Blake, he was also one of the central influences of the early spread of Swedenborgian thought in London during the late eighteenth century and one of the founding members of the Swedenborg Society.

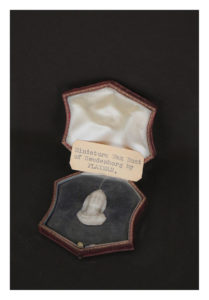

Flaxman is ‘my friend and companion from eternity’”. William Blake

It may well have been Flaxman who introduced Swedenborg’s books to Blake, and it was certainly Flaxman who did much to arrange Blake’s three-year stay at Felpham on the Sussex coast (the only time Blake and his wife ever lived outside London). In a letter from Felpham Blake addressed Flaxman as the ‘sublime archangel’ and ‘my friend and companion from eternity’. The miniature wax portrait of Swedenborg shown here is undated and most likely made as a template for a small cameo head of Swedenborg, ‘cut in sardonyx in very full relief’, from the hand of Giovanni Giuseppe Caputi and arranged by C A Tulk. The nose and the hair are slightly worn suggesting that, at some stage, it may have been handled on a regular basis. Other items from the estate of Flaxman in the Collection include the silver ink stand (top) and a marble font.

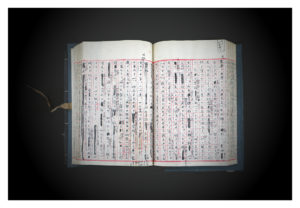

11. D T Suzuki: manuscript notebooks of Tengai to Jigoku (Heaven and Hell)

Widely credited with introducing Zen Buddhism to the West—and influencing writers and artists as diverse as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Gary Snyder, Allan Ginsberg, Carl Jung and John Cage amongst others—D T Suzuki was also the first translator of Swedenborg’s books into Japanese.

“The translation was completed in an intense period of just over 12 weeks in early 1909, in rooms in Great Russell Street, opposite the British Museum”

Recommended to the Swedenborg Society by the Japanese Embassy in London in early 1909, Suzuki was commissioned to translate four works, the first being Tengai To Jigoku which we know in English as Heaven and Hell. Correspondence between Suzuki and the Society shows that the work was completed in an intense period of just over 12 weeks in early 1909, in rooms in Great Russell Street, opposite the British Museum and close to the Society’s then headquarters in Bloomsbury Street. Although the Society still holds over 40 letters and other items from the hand of Suzuki, and some of which were only recently identified, Tengai To Jigoku is the only manuscript of Suzuki’s translations of Swedenborg’s works still extant. Hand sewn and bound in blue rice paper, the notebooks are written in beautiful Japanese Kanji and contain over 1000 handwritten pages, with multiple markings and revisions.

12. Josephine Butler: Letters for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts

ALONGSIDE MILLICENT FAWCETT and Emmeline Pankhurst, Josephine Butler is one the most influential figures of the nineteenth century social reform movement. Not only did she campaign tirelessly for the emancipation of woman’s suffrage but she was a leading activist against child prostitution and the founder of the International Abolitionist Federation which appealed against the illegal trafficking of women and children.

“One letter even touches upon a delicate matter regarding the first ever President of the Local Government Board in 1871”

The eight letters held in the collection, addressed to Dr J J G Wilkinson, were written around 1873 on headed note paper of the Ladies association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. The discussion between the two moves freely between topics including the suffragette movement, the all women college in Newnham and the setting up of a safe house for unemployed women in Liverpool. One letter even touches upon a delicate matter regarding James Stansfeld (1820–98), a British politician who was appointed the first ever President of the Local Government Board in 1871, and a matter to be taken to the cabinet. The eight letters make up only a fragment of the correspondence between the two.

13. T E Lawrence: signed copy of Heaven & Hell

THE FINAL ITEM in this list is, perhaps, also the most unexpected. T E Lawrence, or Lawrence of Arabia, remains a mythic figure in the history of the twentieth Century. Military leader, author and inspirational force behind the Arab uprising against Turkish arms, he was clearly a gifted military strategist and also one of the most influential letter writers of his generation. Not much is known of his interest in mysticism though, and his interest in Swedenborg in particular might be a surprise to many. Nothing is known of when or how he came across this 1909 Dent edition of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell, and beyond his signature on the flyleaf, there are no other references from his writing pointing to his interest in the Swede. A handwritten letter of authenticity, by T E Lawrence specialists John and Edward Bumpus, dated 1957, accompanies the book.

THE FINAL ITEM in this list is, perhaps, also the most unexpected. T E Lawrence, or Lawrence of Arabia, remains a mythic figure in the history of the twentieth Century. Military leader, author and inspirational force behind the Arab uprising against Turkish arms, he was clearly a gifted military strategist and also one of the most influential letter writers of his generation. Not much is known of his interest in mysticism though, and his interest in Swedenborg in particular might be a surprise to many. Nothing is known of when or how he came across this 1909 Dent edition of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell, and beyond his signature on the flyleaf, there are no other references from his writing pointing to his interest in the Swede. A handwritten letter of authenticity, by T E Lawrence specialists John and Edward Bumpus, dated 1957, accompanies the book.

“Military leader, author and inspirational force behind the Arab uprising but almost nothing is known of his interest in mysticism”

Words © The Swedenborg Society/Stephen McNeilly, 2021; photographs © The Quinn Fizzlers, 2021